This article was first published in "The Power of How" by Daniel McGowan.

Baby-Bending

This part is about the huge evolutionary significance of that incredible conscious act that we all performed, of coming up on to two feet, thus changing from a quadruped to a biped, and then, as babies, performing all variations of the movements of bending down and up again co-ordinatedly in the daily round, using the hip, knee and ankle joints, as they are designed to be used, and maintaining the integrity of the head-neck-back relationship. These movements I call “baby-bending”. Sadly, by the time we reach adulthood most of us have lost this conscious co-ordination.

“Oh yeah, Alexander Technique, that’s that queer method where they teach you how to stand up and sit down properly.” This is a typical misconception that many people have about the Alexander Technique – a better name for which is “constructive conscious control”. There is, however a great deal to be gained from learning how to perform the movements of standing and sitting – and any other movement – in a consciously, co-ordinated way, for the following reasons.

“Oh yeah, Alexander Technique, that’s that queer method where they teach you how to stand up and sit down properly.” This is a typical misconception that many people have about the Alexander Technique – a better name for which is “constructive conscious control”. There is, however a great deal to be gained from learning how to perform the movements of standing and sitting – and any other movement – in a consciously, co-ordinated way, for the following reasons.

One of the most harmful movements we learn in early life is to bend down to pick something up from the floor by bending the back in an excessively round manner – mainly in the lumbar region – keeping the legs straight and strongly pulling the head back and down into the shoulders by shortening the muscles at the back of the neck. These movements are a gross misuse of the body and yet they are considered by many physical training “experts” as highly desirable things to do. Such movements have been encouraged in many physical training programs, because it is considered that they will bring flexibility to the stiff person and maintain flexibility in the person who already has it. This way of bending becomes a very strong habit that persists throughout a whole lifetime.

Consider, however, what is actually happening during this grotesque movement. The person is attempting to bend the knees backwards – something they are not designed for – and bend the lumbar spine to an extent that is outside the safe range of movement that the intervertebral discs can allow without being damaged. The hip joints – which should always be used when bending in conjunction with the knees moving forwards – are hardly bent at all. This is one reason – among many ways of misusing the body – why damage to the two lowest discs in the spine is one of the most common ailments in the world.

Another negative result of bending the back to an excessive degree is that all the vital organs in the torso are harmfully compressed and this can lead to malfunctioning, which leads to dis-ease and ill-health.

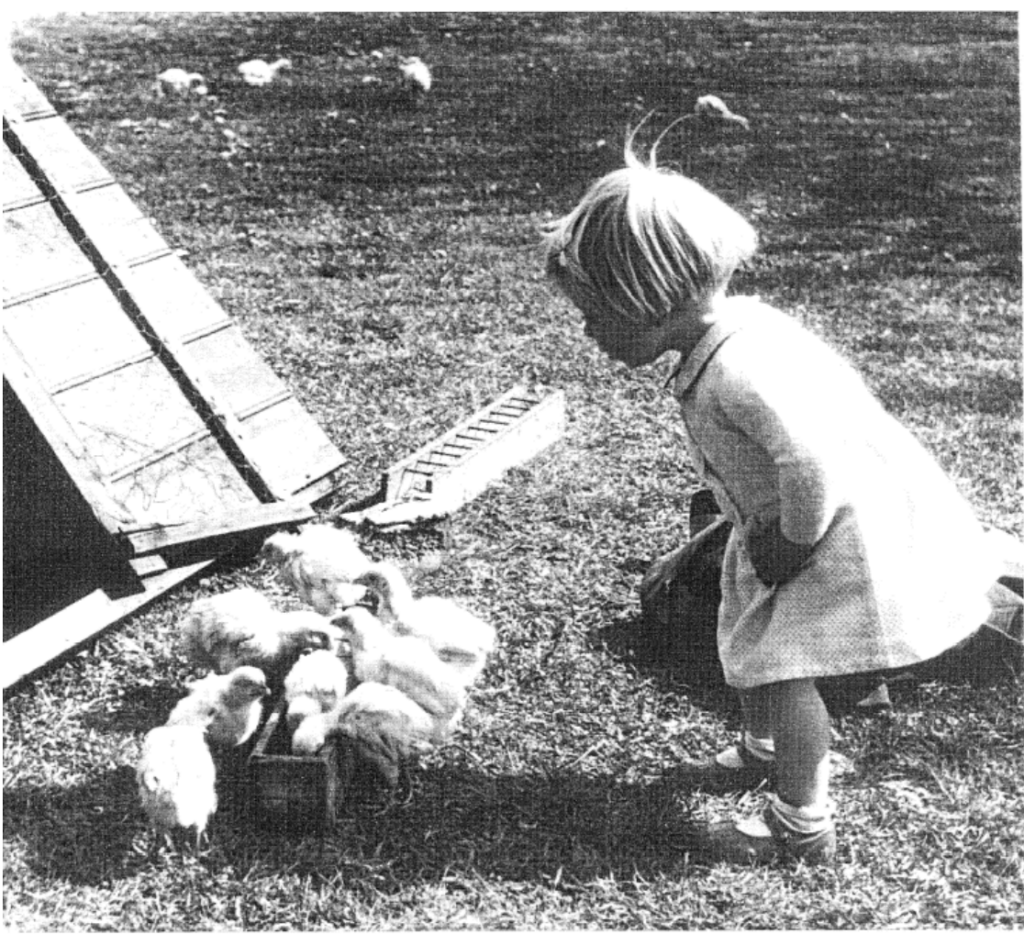

There exists, however, a group of human beings who do not misuse themselves when bending down into a deep squat and straightening up again to standing – babies! These lovable creatures perform these movements naturally and gracefully by allowing their knees to go forwards and hips to go backwards, as well as maintaining the integrity of the head-neck-back relationship by allowing everything above the hip joints to remain virtually undisturbed. Even if the baby’s head rotates backwards at the atlanto-occipital joint, say to look at something above eye-level, this is done in an easy, natural and co-ordinated manner that causes no harm.

Considering in particular the movement from squatting to standing, let’s look at the evolutionary significance of the first time the baby performed this movement. From the moment he was born, he was driven by evolutionary compulsion to fulfil an inward need that he had recognised: a need that brought out his creativity, which in turn would fulfil that need. Such a need was satisfied when he used his creative powers to learn how to turn over from lying on his back to lying on his front. The next need he felt was to get on to hands and knees and subsequently to crawl around: both being acts of tremendous creativity. Next came the need to get up from this situation and stand on two feet. This wonderful act was performed by taking his knees forward and up off the floor so that he was now supporting the body on his hands and feet, which were now quite close to his hands. He then performed the amazing act of taking his hands off the floor, straightening his legs and bringing the torso back and up until he arrived at the upright situation of standing on two feet. The significance of achieving this feat could not be overstated. In that one magical movement he changed from a quadruped to a biped; another act of tremendous creativity.

Bearing in mind that the baby had to learn how to remain upright, he had performed a movement that was now the basis of every other movement he would make in the rest of his life. He would now repeatedly fall down when he lost his balance by letting his knees go forward and hips go back until his bum plopped gently on to the floor. Despite appearances babies are very good at allowing themselves to fall and they very rarely hurt themselves. When the baby thinks he can maintain the upright situation, he then attempts to walk: I’ll come back to this later.

The reason that I use a chair as one of a number of teaching aids in my lessons is because most adults are so badly misused they can no longer go into a deep squat easily and come back up to standing, as natural-living humans do. The chair was invented because of this inability, caused by misusing the body. It is probably the most atrocious invention in history. It is not all bad, however, because when a person wishes to stop misusing themselves and seeks the help of a teacher of constructive awareness in order to re-learn how to stand up and sit down in the co-ordinated manner of the baby, he only requires to go about halfway up in rising from the chair and halfway down when descending to it. This co-ordinated way of performing, in particular, the movement from sitting to standing stirs the kinesthetic or proprioceptive memory of performing that first fundamental magnificent feat of coming up from a quadruped to a biped. Standing up from a chair, or sitting down into one in a lesson has nothing to do with standing and sitting, as done habitually and harmfully by most people. It is simply about re-learning how to move consciously and co-ordinatedly in a mechanically appropriate manner in harmony with the way the body is designed to move. The chair is almost incidental and is merely there to provide a stopping point, a halfway house, for the person who cannot squat all the way down.

Constructive conscious control teaches us how to react reasonably and co-ordinatedly to the countless stimuli of life coming at us relentlessly in daily activities. Our reactions to these stimuli are habitually too fast and ill-considered, mentally, physically and emotionally. Considering physical movement, during a lesson the teacher gives the pupil a stimulus by asking her to sit down, but before doing so to stop and consider that the appropriate way to do this is to let the knees bend forwards, the hips go backwards and the torso to incline forwards in space. The pupil is then asked to give attention to the act of moving downwards in space, asked to ignore the chair while remaining in the moment and consciously bending as described above until the bum arrives on the chair. As I said earlier, the chair is incidental and is merely there to provide a stopping point. Nonetheless, because of our habitual way of reacting too quickly to stimuli and because we are inveterate end-gainers, the chair is always there inviting the unthinking body to collapse into it: always there inviting him to forget to stop and consider the most mechanically appropriate way to sit on it. The chair is, therefore, what I call the eternal stimulus.

Considering the act of rising from the chair, the pupil starts from a point that is about halfway along the path of that amazing movement the baby made in moving from all-fours to become a biped. The teacher asks the pupil to stand up, but before doing so, to stop and consider the most mechanically appropriate way to do so with minimum effort. This is done by ensuring that the feet are flat on the floor and placed under the knees or a little behind them, depending on what the pupil can manage. If the feet are placed too far forward, the pupil will be unable to stand up. The teacher guides the pupil through the co-ordinated process of allowing the torso to incline forward from the hip-joints, while allowing the back to be as close to its optimal length as possible, until a point is reached where the legs must come into play to perform the act of coming up to standing. Thus, at least half of that crucial evolutionary act of moving from all-fours to standing on two feet has been performed in the way the body is designed to do it: that is, by articulating at the hips knees and ankle joints and not bending and shortening the torso.

These two movements of sitting and standing with conscious, co-ordinated use of the body are enough in themselves to re-educate the whole neuromuscular system, provided they are repeated often enough. The importance of repeating them under the guidance of the teacher’s hands could not be overstated. These are fundamental movements that allow the pupil to get in touch with his kinesthetic sense and to gradually become familiar with it: so familiar with it that eventually he will not need the help of the teacher. A word of warning! Repeating these movements does not mean doing so in the rapid-fire, over-vigorous, mindless way in which most people perform mechanically inappropriate gymnastic exercises, physical jerks etc. They must be done slowly and consciously with the help of a competent teacher.

It must also be emphasized that these co-ordinated movements are not only mechanically appropriate ways of moving – although that would be beneficial anyway – they must be preceded by certain thoughts or directions to the body before going into them. Foremost of these thoughts is the refusal to react too quickly to the wish to stand up or sit down by inhibiting the strong tendency to perform the act in the old habitual, misused way. The teacher then tells the pupil how to think certain directions that will maintain the integrity of the head-neck-back relationship – not only during these basic movements – but also eventually in any and every act of daily life. These movements are simply used at the beginning to introduce the pupil to “constructive conscious control” which is the title of one of Alexander’s books.

Constructive Conscious Control – is not an “ism”. It is simply a conscious, co-ordinated way of being and moving and covers the whole gamut of human movement from the “simple” act of moving a finger to the most complex combination of movements, whatever they may be. It is true mindfulness. Psycho-emotional benefits also occur in using conscious control, but I am not covering them in this essay.

Let’s return to that profoundly significant moment when the baby arrived at the upright situation and became a biped. Although in attempting to perfect this ability to stay upright the baby fell down many times, he was now experiencing being a biped more often than a quadruped. In the upright situation he had a great difficulty to overcome that he had not had as a quadruped: and that was to learn how to balance the head on top of the spine. In relation to the rest of the body, the baby’s head is proportionally much larger than the adult’s. On reaching the upright situation, his head will naturally and persistently fall forwards, but will be prevented from doing so by the muscles at the back of the neck. This drop-catch process at the head-neck joint causes a ripple of postural adjustment all the way down the back and through the hip, knee and ankle joints. This flowing adjustment throughout the body is usually lost, however, as the baby becomes a child and starts to lose his good use of himself by copying badly misused parents and other adults with similar, faulty co-ordination. The word “postural” is here used to mean a constant, dynamic and natural process of adjustment, starting at the head-neck joint. It does not mean some contrived and fixed position as used, for example, by fashion-models walking around balancing books on their heads. In a consciously co-ordinated body that has appropriate, balanced muscle-tension throughout, this ripple of postural adjustment will always be there, even when standing “still”.

Once the baby is able to remain standing on two feet, he then sets out on the great adventure of maintaining the upright situation as he learns to walk. I will come back to this later. In the meantime, there is another situation that the teacher demonstrates to the pupil, which is that of stopping in mid-ascent as he rises from the chair, but does not go all the way to the erect situation. The pupil has now stopped with his knees bent forward, hips back and torso inclined forward: stopped at a point along the way described earlier of the baby rising for the first time from all fours to balancing on two feet. The teacher then asks the pupil to think certain directions mentioned earlier that will maintain the integrity of the head-neck-back relationship. With his hands the teacher makes subtle adjustments for the pupil that may be necessary to achieve this co-ordinated relationship. While the pupil remains in this balanced baby-bend, the brain gets time to assimilate the information coming to it from the muscles and this stirs the kinesthetic memory of moving and pausing in this co-ordinated way as a child. The re-education of the whole neuromuscular system begins not only in this situation, but also in the acts of moving in and out of the chair described earlier. Repetition of these procedures is necessary for the improvement and refinement of the functioning of the neuro-muscular system. It is worth noting here that while the pupil is in this “stationary” baby-bend, the big extensor muscles in the back, bum and legs are working efficiently just to maintain this situation and, as I wrote above, information of this co-ordinated “position” is being sent to the brain, which – although a bit confused – begins to deal with it. The brain’s kinesthetic memory is stirred even more when this “stationary” situation changes to a mobile one when the pupil decides to either come up all the way to standing, or bend deeper until the bum reaches the chair and the pupil is seated.

In conclusion, the above procedures – right from the beginning – are of the utmost importance in this wonderful, re-educative process of constructive conscious control of the self because they deal with that fundamental movement of changing from a quadruped to a biped; that movement of coming up from all-fours to standing on two feet, which is the basis of all subsequent movements made as a biped throughout a whole lifetime. The reverse of this consciously co-ordinated movement to arrive at being seated in a chair, or to stop at some point on the journey, or, if you can, squat all the way down, is what I call, “Baby-bending”.

Stepping Out

The above explanation of baby-bending would not be complete without going further into the next great need that the baby felt, which was to learn to walk: truly a step into the unknown.

There he was – having arrived at the upright situation and now balanced precariously on two feet – which were quite far apart because he also needed to maintain his balance laterally. While working to keep his head balanced on top of his spine, such process demanding great thought and attention, he had to be brave and move one foot forward. He may have only managed one step before falling down on to his bum, but that was enough to show that he could do it. That evolutionary compulsion that drives every human being urged him to repeat the whole process of rising from all-fours to two feet and taking another step and another and another and another…..As he repeats the process of taking one step after another he learns to bring the feet closer together laterally as he calls on his ancient memory of balance via the vestibular apparatus in the ears and receptors in the muscles all over the body.

This means that during this period of development, the baby’s brain is probably dealing with more kinesthetic information from the rest of the body than he will ever handle in the rest of his life. If he is left alone to pursue this great adventure of exploring these inborn capabilities he will make rapid progress. In general, however, there are two great obstacles that block the baby’s smooth process of refining his movements. These two obstacles are called parents.

The parents are usually there displaying nail-biting anxiety and enthusiastic anticipation at that magical moment when the baby takes those first few hesitant steps. The baby’s apparent – not actual – clumsiness is mistaken by the parents to indicate that the little one needs help. Most parents cannot curb their enthusiasm and if they feel the toddler is not progressing quickly enough, they will take him by the hands or arms and half-drag him across the floor, with the result that the baby flaps his legs back and forward in a futile attempt to contact the floor with his feet. This is a gross interference by a misused adult on the little one’s finely tuned neuromuscular and kinesthetic systems.

No matter how well-intentioned the parents may be – after all, we all love to think how special our own child is and wish fervently for him to progress as quickly as possible – they cannot help but impart their end-gaining misuse to the co-ordinated organism of the toddler. The baby is so sensitive that he picks up the clumsy habits of movement that the parent has developed during his or her lifetime.

The vicissitudes of life have brought the parent to a state of misuse that manifests as habitual, harmful, malco-ordinated muscle-tension patterns throughout the body. Parents are not to be blamed for this misuse: they simply do not know they have it. This habitual misuse is passed on to the finely tuned organism of the baby and is the start of the toddler learning to misuse himself by copying the parents. While the baby is going through this whole evolutionary process from lying on his back to turning over on to his front, to coming up on to all-fours, to coming up on to two feet, to finally walking, parents would do well to leave him entirely alone to find his own way.

The baby knows what to do, and apart from making sure that he stays clear of dangerous objects and hard, sharp-edged furniture, the parents should leave him to his own devices. As I said, despite appearances, the baby is not clumsy, but is going through a highly skilled process of calling on his ancient memory – which we curiously call instinct. Even plopping down on to his bum without hurting himself is a skilled act springing from this ancient memory. He is working with the kinesthetic sense and needs no help from a misused adult to do so. The apparent ease with which he walks as an adult is achieved through these “clumsy” efforts he made during the whole learning process. The process itself cannot, therefore, be a clumsy one.

Another situation where the child’s co-ordinated use of himself is badly interfered with occurs when he can walk reasonably well at around two or three years old, and is walking hand in hand with a parent who is in a hurry and is unwittingly pulling his body harmfully to the side via the arm. This can cause a lateral twist in the little one’s spine as well as an imbalance in the use of the muscles of the back on each side of the spine. I am not saying the parent should not hold the child’s hand – the child may even want to do so – but the parent must be careful not to upset the toddler’s good use. Sadly, however, many parents have no idea that they are interfering with the child’s co-ordination, and causing harmful, imbalanced muscle-tension patterns that will last for a whole lifetime. These negative patterns can also cause psycho-emotional problems that endure for a lifetime.

This article was first published in The Power of How by Daniel McGowan. You can download the PDF of this book for free here: FREE DOWNLOAD