This article was first published in "Going Mental" by Daniel McGowan

Walking and Upright Standing

Figure 1

Figure 1

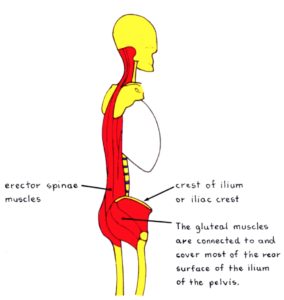

Let’s now consider the role of the pelvis and the muscular attachments to it. A perusal of them shows that the muscles attaching from the legs are given priority over those from the torso. Most of the front surface of the ilium is covered by the iliacus and psoas major muscles and the gluteal muscles do the same on the rear surface of the ilium.

You can see these muscles in Figure 1 and Figure 2. They form a sort of lap joint with the ilium, rather like when you lengthen your fingers and put the palms of your hands together. You can spread lots of super glue over this large area of contact! This large area is needed because of the great forces thrown into the pelvis during walking and even more so in running.

Figure 2

If you look at the muscles from the torso, the quadratus lamborum, for example, you will see that they have a more tenuous connection with the crest of the ilium, and form a sort of butt joint, rather like putting the edges of your hands on the pinky side together. You can’t get so much super glue on this smaller area of contact. This small area of contact with the ilium is one of the reasons why so many hernias occur.

Not only the pelvis, but the lumbar spine is subject to tremendous forces from the psoas major muscle, which is the only one that runs up above the top of the pelvis from the legs and connects to the lumbar spine. All the other muscles running up from the legs attach to the pelvis and do not continue above the iliac crests.

This shows that priority is given to the muscles that perform the most common and most necessary act that all of us have to do – WALKING. Even the large adductor muscles on the inside of the thighs have more tenuous connections to the pelvis at the front and at the sitting bones. We cannot move the legs laterally out and in as powerfully as we can forwards and backwards. Going back to the standing situation, the intrinsic semi-rigid structure of the spine means only a small amount of muscle effort is required to keep it erect, in contrast to the considerable muscle power necessary to keep the legs in place under the pelvis.

We have then, through our wonderful creative abilities, developed the pelvis to form a rigid structure of bone, capable of handling these powerful forces from the legs. As I said earlier it is not a basin for carrying the abdominal contents. The vital organs in the torso are suspended from the spine and rib-cage, hence the importance of allowing the spine to function at its optimal length.

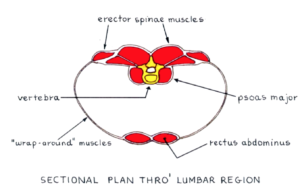

We can now see the close interaction of the muscles that form a central band in the torso, consisting of the erector spinae all the way up the back to the head, down through the sternomastoids, the sternum, the rectus abdominus and the perineum muscles. When the pelvis is tilted forward by the action of the iliacus when moving a leg forwards and the lumbar spine is simultaneously pulled forward by the psoas major, then provided the spine is at its optimal length, the rectus abdominus will react immediately by contracting to counteract this.

The fact that this muscle is an active participant in the act of walking is the reason why it is given priority over the transverse abdominal muscles, which have a hole in them to let it run through from the sternum to the pubis. The rectus abdominus is intersected along its length by horizontal tendons that make it look like a chocolate bar on the body builders. The reason for this is that the distance from the sternum to the pubis is considerable and because muscle is so elastic and stretchable, these tendons are required to stop the rectus abdominus from stretching too much, otherwise it could not effectively counteract the tilting of the pelvis during walking and running.

It is interesting to see that the only area where the leg muscles overlap with the back muscles is over the length of the 5 lumbar vertebra, the psoas major running up as far as the 1st lumbar vertebrae and the erector spinae muscles that hug the spine, running down and over the sacrum. Here the lap-type of connection of the erector spinae muscles with the sacrum is given priority over the butt-type connecting the muscles that surround the abdominal cavity. You can see a transverse section of these muscles in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Figure 3

In summary we have a central band of muscles running up and down the front and back of the torso, which, because of their more direct reaction to the powerful forces generated by the legs in walking and running, are given priority over the muscles that surround the abdominal cavity.

The power needed in the large muscles that human beings have developed, not only for maintaining the upright stance, but also for running and walking, can be more easily appreciated if we compare ourselves to the monkeys. We have big bums and monkeys don’t! One reason why the monkey cannot stand or walk upright is because s/he does not posses the big powerful gluteal muscles that we have created.

The act of coming to the upright situation was one of tremendous human endeavor and was performed mainly by the gluteal muscles, which had to become big enough and strong enough to haul the torso up to the vertical over the legs. This upright stance was achieved by the relentless repetition of the attempt to stand up and of refusing to stay down when we fell down, again and again. And why did we stand up? Because we wanted to, we felt the need to do so.

When you were still a reptile walking around on all fours, you suddenly had the wish to play the piano, or paint a picture, or plough a field and after millions of years and many reincarnations, you achieved your goal by learning how to stand up and free your forelegs for doing wonderful things.

The state of being upright has not been achieved by any other creature on the planet. Neither has the ability to oppose the thumb to the fingers, another amazing creative achievement. Another reason why the monkey does not stand upright is because, at the moment, s/he does not have the wish to do so. The human had the wish and stood up as a result of it.

This article was first published in Going Mental by Daniel McGowan. You can download the PDF of this book for free here: FREE DOWNLOAD